Eye For Film >> Movies >> The Fifth Season (2012) Film Review

The Fifth Season

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

The other day I found a winged ant in my bathroom. Not the right shape to be a queen. In January. Sometimes things happen out of season and it's startling. An anomaly or an indication of bigger changes at work? A reminder, perhaps, of how much we take for granted.

Nowhere does the pattern of the seasons matter more than in farming communities. That may be why it is in agrarian villages that the old pagan customs have lingered longest. Their archaic nature makes them look bizarre to outsiders. The locals usually get the joke but find the rituals fun, cheering and important to community cohesion. Here giant male and female figures parade through the streets, collecting followers. Everybody goes to the top of the hill where a bonfire is ready to burn old Uncle Winter, made of straw. Thierry, who has just turned 18, has the honour of lighting it. But when they pyre refuses to be set alight, concern grows rapidly. Is this just an anomaly, or the start of something terrible?

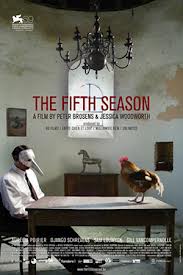

Within days, it's apparent that things are going very wrong indeed. The bees have died. The seeds in the field won't germinate. The cows have stopped giving milk and stubborn old Fred the cockerel won't crow, no matter what his master does. The spring trees grow no leaves. We have entered the fifth season, and soon it is apparent that the problem extends far beyond the village itself, leaving people with nowhere to turn.

Not since John Christopher's novel The Death Of Grass has anyone taken on these issues on quite this scale. The Fifth Season is well aware of its roots in literary and cinematic tradition and doesn't patronise us by expecting us to be surprised at the developing story. Rather, it depends on a sense of inevitability, of the weight of impending doom that is as much moral as corporeal. Its references to famous paintings, alongside the playful imagery of surrealist cinema, provide a historical context that makes the film as much a comment on art as on politics or human nature. They also serve as a reminder of the scale of the civilisation under threat, or how much can be achieved without ever making us less dependent on those first things we learned to worship - the sun, the rain, the earth.

The political context is, of course, the worldwide economic recession - a fifth season of sorts, as familiar structures break down, cycles collapsing, leaving people desperate and unsure what to do. Most potently, as the vllagers squabble over whether or not they should share the food they have left, we see the concept of solidarity raised, distorted, in opposition to fraternity. It doesn't take long for social niceties to disappear. Who cares if the neighbours are starving? One can always persuade oneself that they deserve it.

Inevitably, of course, the villagers start looking toward the pyre on the hill and wondering, as their rationality slips away, whether they ought to make a more potent kind of sacrifice. They are beginning to think symbolically, just as the film is laden with symbols atop a washed-out colour palette. Its individual characters are few and we see them more than we hear from them; individuality is rare, struggling to express itself or perhaps seeing little point in doing so in the face of the inevitable. Only a single act of kindness punctuates the closing scenes. Is it too late?

Reviewed on: 30 Jan 2013